From the Denton Record Chronicle.

The University of North Texas

The Founding

In 1890, ten Denton businessmen formed what became known as "the Syndicate" to establish a normal school - a college that would train teachers -- in Denton. They bought 240 acres west of -- it was later annexed by the city -- to develop into blocks, lots and streets and donated ten acres to the city as a campus for a new college. That ten acres became what is now the sprawling and growing University of North Texas campus.

Citizens approved $15,000 in bonds for the school and the following year, the cornerstone of the first college building was laid with great ceremony by Masons, as was customary. As historian Edward F. Bates described it, "a great concourse of people gathered at the city hall" (which was then on the downtown square) and marched to the grounds, led by the Masons, city officials and Joshua C. Chilton school. Fire destroyed the building in 1907.

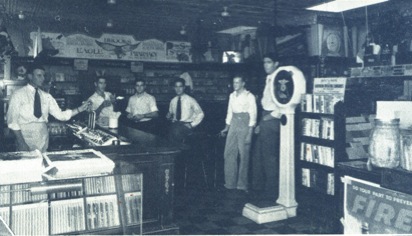

City officials had contracted with Mr. Chilton to operate a nine-month school, which already was in temporary headquarters on the second floor of the building that now houses Thomas Furniture Store on the northeast angle of the square. The faculty was Mr. Chilton, John M. Moore, later a Methodist bishop; Dr. J.W. Dealy, later editor of the Dallas News -- now the Dallas Morning News; and C.E. Sargent, Jesse A. Sanders, and Mrs. E.J. McKissack.

Enrollment fell short of expectations and there were financial problems. Mr. Chilton resigned in September 1893 because of health problems and died the following February. A contract then went to Professor Minter B. Terrell, who began his term as president with three faculty members. Problems of low enrollment and not enough money continued, however, until the city took steps to change the school into a free state college.

After several unsuccessful attempts, a state school was finally authorized in March, 1899, by the Twenty-Sixth Texas legislature. approved an act creating a state normal school for the "special training of teachers." They named in North Texas Normal College. Denton agreed to donate all the Normal School property to the state, including land, buildings and an "abundant supply of artesian water."

When it opened for registration in September 1901, the school had 14 faculty members, including the president, and about 200 students.

At the time, state regulations required that a student applying for any class had to pass a test on the next lower class in the same subject. In 1917, the state adopted standard regulations for all normal schools: a student must be 16 years old or over; a first year student must have completed seven "admission units," one or two in algebra, two in grammar and composition, one or two in history and enough electives to make seven units. A unit was five 45-minute lectures a week for three months. There were various exemptions, of course, including one that in effect allowed any student who had completed the ninth grade in an approved high school to enter the normal school without meeting the specific unit requirements.

By that time, the college offered seven courses that prospective teachers could take. Agriculture covered teaching biological and physical sciences, as well as agriculture, and was designed particularly to train principals of consolidated schools and rural high schools.

The Home Economics course was for women only. Other courses were Manual Training, Language, Science - which covered mathematics and science in high schools -- Primary and Arts, and History-English.

A student could earn a Normal School diploma after completing the fourth or senior year of studies and a bachelor's degree after completing two more years of advanced training.

Students also organized literary, musical, debate and other organizations. There was a band, chorus, and school publications. Students were expected to participate in extracurricular athletics, overseen by an Athletic Council made up of a faculty committee and a students' association. The duty of the council, according to Mr. Bates, was to "keep athletic interest in the school not only alive and healthy, but sane and intelligent as well."

Water

When the city of Denton turned over what was then North Texas Normal College to the state of Texas, the legislation required the city "to furnish …an abundant supply of pure artesian water free of cost to the State, for all the purposes of said school."

That pledge lasted only about 50 years.

In 1912, the city's water superintendent notified the school that city water to the school -- now the University of North Texas -- would be cut off because the school was using too much water. That threat ended when college president Dr. W.H. Bruce reported that the city of Oak Cliff in Dallas County had offered land and buildings if the school would move there.

The water issue was dropped.

However, it became a full-blown controversy in the 1940s when the city faced more serious water shortages, according to a history of the university by Dr. James L. Rogers.

In a letter dated Oct. 16, 1945, City Attorney Earl Coleman told college president, Dr. W. Joseph McConnell that the city commission could not legally enter into a "perpetual contract" such as the water contract and was "thus furnishing water to your State Institution without any authority to do so."

Dr. McConnell responded with a three-page letter countering the city's position but offering to talk further about the issue. He then asked the Texas Attorney General for an opinion.

The Attorney General ruled the contract valid and that the city was legally bound to furnish water to the school free of cost. However, the college should not furnish auxiliary water to self-supporting dormitories, the ruling said.

The issue was settled, according to an article in the January 22, 1946, Denton Record-Chronicle. But not for long.

In March 1947, Denton Mayor J.L. Yarbrough notified the city commission that it "was imperative and a public necessity " that the two state schools in Denton pay their water bills. North Texas owed $8,599 and the Texas State College for Women -- now Texas Women's University -- owed $29,790, according to the mayor.

President McConnell responded with a reminder of the Attorney General's opinion, adding that the eollege had paid for the auxiliary water to the dormitories -- in fact had paid $16,172 too much.

As the water shortage continued, the mayor notified Dr. McConnell that water to the college swimming pool, athletic field and outside grounds would be cut off on July 29, based on a city resolution. The resolution also said that no new connections would be made to the school. City attorneys said the action was necessary because the state of Texas would not cooperate by letting a court decide if the 1899 agreement was valid. City officials later admitted that their threat was an attempt to force the college to file for an injunction against the city and thus get the issue into a district court.

The issue again was referred to the Texas Attorney General. The city did not cut off water to the college after learning that the cut-off also would eliminate water to other buildings.

Two days after the aborted cutoff deadline, the city adopted another resolution to again try to force the issue into the courts. This time, the cutoff deadline was August 28, 1948. Again, the college board of regents referred the issue to the Texas Attorney General, and this time he filed an injunction that would give the city its day in court.

That day never came, however. As negotiations continued between the state, the college and the city, State Representative Hal Jackson of Denton submitted a legislative bill authorizing the college's Board of Regents to contract with the city of Denton for water. The bill passed.

In May 1949, the Denton City Attorney notified college officials that the city would bill North Texas for water at commercial rates.

Desegregation

The University of North Texas, continuing its year-long celebration of the historic Supreme Court ruling 50 years ago that ordered desegregation of the nation's schools, brought together enough athletic prowess last Saturday to probably lift the Gateway building where they all congregated.

Fifty years of history, multiplied by about 150 athletes, was there. UNT had awards for every African American athlete who broke racial barriers in every sport and the women who broke both racial and gender barriers after another far-reaching ruling in 1972 that prohibited discrimination against women in athletics. Bill Mercer, the voice of North Texas for nearly 50 years, was emcee.

Abner Haynes and Leon King, who integrated the North Texas freshman football team, and James Bowdre, who joined them the next year to make it three African Americans on the varsity team, were there.

So were the many who followed them and won conference and national recognition on the football field and basketball court, at track and field events and other sports, many like Joe Greene, J.T. Smith, and Charles Beatty who became professional football superstars, .all the way up to the current crop of athletes who hold university and conference records in their respective sports.

Also at UNT Saturday were two of the coaches from 1956 - Fred McCain and Ken Bahnsen. (FC). The story of integration at North Texas wouldn't have had the same ending without the coaches.

The story has been told of Haynes and King, how they walked on to the football field in 1956 to join the freshman team, the threats and indignities they faced, their courage and perseverance. Haynes went on to professional football fame. King became an educator and earned his Ph.D in education at North Texas.

Ronald Marcello, associate history professor at North Texas and director of the oral history collection, studied the integration of North Texas for an article that he wrote in 1987 for the Journal of Sport History. Marcello described a situation where the right people came together at the right time in history to make integration work.

There were the two outstanding athletes. There was North Texas president J.C. Matthews, an authoritarian who was determined to prevent violence and the publicity that he believed prompted violence, on campus. There were freshman quarterback Vernon Cole, his older brother Charlie Cole and junior Garland Warren, who planned well ahead of time to welcome the two African American men, and other players who followed their lead.

And, there were four coaches who led the way.

Incredible as it may seem, North Texas had only four coaches in 1956 for all sports. Odus Mitchell was head coach. McCain, Herb Ferrill (FC) and Bahnsen were assistant coaches. That was it, the full coaching staff.

"To a large degree, acceptance of the black players rested with Odus Mitchell through his three assistants," Marcello wrote.

Mitchell had a reputation as soft-spoken and even handed, a man who gave everyone an equal chance. He also knew that he faced a potentially volatile situation. Mitchell met with his staff regularly to decide on several tactics to avoid trouble.

First, they didn't ask the white players if they wanted to play with blacks, they simply assumed the right of blacks to play without the need for explanation. Second, they encouraged the viewpoint that integration could help their team win a conference championship --- which it did. And third, the coaches agreed that hard hitting in practice, as usual in testing new players, was acceptable, but no cheap shots would be tolerated.

Fifty years later, it is an amazing plan. They treated the two young black men like everyone else.

Bahnsen was freshman coach and - again as incredible as it seems - was the only coach who traveled with the freshman team to games. He and the bus driver. When the team encountered a screaming, rock-throwing mob in Corsicana. Bahnsen had all the equipment put on the bus during the last quarter of the game and players ran for the bus, with Haynes and King protected in the middle, to make a fast getaway. The mob threw rocks and bottles at the bus as they sped away.

Incidents like that bonded the team, Bahnsen told Marcello. When restaurants refused to serve the black players, white members of the team refused to eat without them. Once or twice, the team had take-out fast food at a city park. Once they ate bologna and bread on the bus.

Integration would have come to North Texas in some way, no matter what happened in the athletic department in 1956. But it wouldn't have happened the same way. It was another ten years before the Southwest Conference had integrated football teams.

Every athlete at the Saturday celebration owes a bit of his or her success to those first two African American players and the coaches, the 1956 teams and the school that made it happen.

NITA THURMAN, a Shady Shores resident and journalist, is a member of the Denton County Historical Commission. Her e-mail address is nitathur@aol.com.)